PP 2 | Digital Access

Digital Access

Digital Implementation in Europe: Availability, Innovation Sources, and Structural Constraints

Europe’s digital transition is guided by an explicit, continent-wide strategy—the European Commission’s Digital Decade 2030—which sets concrete targets for skills, infrastructures, businesses, and government services. The EU aims to scale up fiber and 5G coverage, raise basic digital skills, and make public services digital by default; these programmatic goals shape public funding, regulation, and national broadband plans across member states.

Device and connectivity availability

At the aggregate level, European households and individuals enjoy very high levels of online access and device ownership compared with most of the world. Eurostat reports that roughly 94% of EU households had internet access in 2024, and the gap between urban and rural household access has narrowed substantially (in 2023, roughly 95% of city households, 93% of towns/suburbs, and 91% of rural households had internet). Smartphone ownership and mobile subscriptions are widespread across the region. These figures show that the basic physical prerequisites for digital participation—devices and network access—are widely available for a large majority of Europeans.

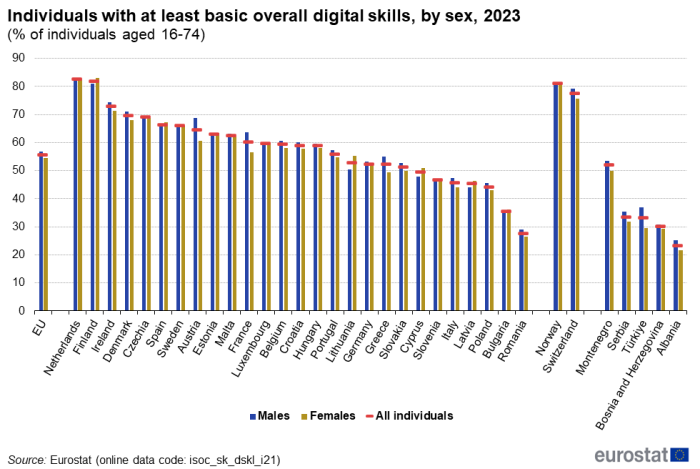

Availability, however, does not mean uniform affordability or effective use. International monitoring of ICT prices finds that while ICT services have generally become more affordable globally, there remain affordability and take-up differences within Europe: poorer households, older citizens, and some southern or peripheral regions lag in device replacement, fixed-broadband take-up, and basic digital skills. In other words, coverage is high but pockets of cost-sensitivity and low demand persist; policy must therefore address both supply (networks) and demand (costs, devices, skills).

Who drives digital innovation: governments, corporations, or both?

Innovation in Europe is clearly hybrid: national and EU institutions set regulatory frameworks, fund infrastructure, and develop common public-sector platforms, while corporations and startups deliver most consumer services, hardware, and many technological innovations.

On the public side, the EU’s Digital Decade and the Digital Decade Governance Programme (plus national broadband plans) provide the policy architecture and funding incentives (including substantial post-2020 EU budgetary allocations) for fiber and 5G rollouts. The European Commission also spearheads regulatory reforms (e.g., the Digital Markets Act, Digital Services Act) intended to shape platform behavior and competition. At national levels, governments fund or subsidize broadband in unprofitable rural areas and operate digital public goods (e-ID schemes, e-government portals) that enable private players to build services on top.

Private companies—telecom operators, cloud providers, device manufacturers, and startups—drive most product innovation and deployment speed. Operators invest in physical networks (fiber, 5G) and experiment with alternatives (satellite broadband, fixed wireless). Large cloud and platform firms provide the software stacks and services that Europeans use daily, while startups create new apps and business models that government platforms can enable or regulate. The interplay—government sets rules and funds base infrastructure; industry builds, competes, and innovates—dominates Europe’s model.

Geography, finance, and structural constraints

Europe benefits from several structural advantages: relatively high population density in many countries (compared to e.g., the United States), strong regional markets (single market effects), and substantial public funding options through EU instruments. These features make last-mile investment more economically feasible in western and central Europe than in many other regions.

Yet geography and finance still matter unevenly across Europe. Large differences exist between north/central Europe (high fiber and VHCN coverage, faster take-up) and parts of southern and eastern Europe where fixed very-high-capacity network (VHCN) coverage and 100 Mbps take-up lag. The EU’s 2024 Broadband Coverage Report confirms that while many countries reach high nominal coverage, take-up (households actually subscribing at high speeds) lags in places—pointing to demand and affordability, not just physical absence. Moreover, countries with weaker public finances or slower growth (for example, structural challenges documented in Italy’s 2024 reporting) show lower levels of firm-level digital adoption and skills, which inhibits the domestic market for advanced digital services.

A related structural concern is telecoms’ commercial sustainability. Falling consumer prices—generally good for users—have squeezed operator margins in some markets, raising questions about long-term investment incentives unless regulators and policy designs maintain healthy competition and fair returns for infrastructure providers. Recent industry reporting warns that price pressure may reduce operators’ capacity to sustain large capital expenditures without supportive regulatory or subsidy frameworks.

Hard evidence: what the numbers show

-

Household internet access: ~94% of EU households had internet access in 2024 (Eurostat).

-

Urban/rural gap: In 2023, urban household access was ~95% vs rural ~91% (Eurostat).

-

Broadband coverage vs take-up: The 2024 Broadband Coverage Report shows high nominal VHCN coverage in many countries but persistent gaps between coverage and actual high-speed subscription take-up—indicating demand/affordability issues.

-

Affordability trends: ITU analyses show ICT prices have generally become more affordable, but affordability and device replacement remain uneven across socioeconomic groups.

Critique: policy strengths and weaknesses

Europe’s strengths are strategic and institutional: a clear long-term policy (Digital Decade), multi-level funding instruments, and aggressive regulatory action to shape platform economics. These features provide stability and a framework for cross-border services, digital identity, and interoperable public goods.

Weaknesses are mostly executional and distributive. First, take-up / affordability: network availability alone does not guarantee subscriptions—governments must pair build-out programs with affordability subsidies and digital skills training to convert coverage into meaningful access. Second, uneven national capabilities: member states vary widely in digital skills, firm adoption of advanced tech (AI, cloud), and public-sector digitization, producing fragmentation. Third, investment sustainability: intense price competition may hurt operator margins and long-term investment if not paired with sound regulatory incentives and public support where markets fail. Finally, data & mapping quality matters: accurate, harmonized data is essential to target funds efficiently and avoid waste.

Recommendations

-

Pair infrastructure funding with durable affordability and skills programs. Coverage without adoption fails communities; national/regional plans should include device subsidies, low-cost plans, and public digital literacy programs.

-

Encourage demand stimulation in lagging markets. Use vouchers, bundled services (connectivity + content + training), and public-sector digital service rollouts to raise perceived value and drive subscriptions.

-

Protect investment incentives while promoting competition. Regulatory design should balance low consumer prices with sustainable returns for fiber and 5G investors, possibly via spectrum pricing and infrastructure sharing models.

-

Improve pan-European data & mapping standards. Harmonized, high-quality coverage and take-up metrics will ensure EU funds target truly underserved communities.

Conclusion

Europe’s digital implementation strategy is ambitious and institutionally well structured: the Digital Decade gives policymakers a roadmap, and public funding plus regulation mobilize markets and platforms. The continent has achieved high levels of device ownership and internet availability, but important gaps remain in affordability, digital skills, and the economic sustainability of network investment—especially in southern and peripheral member states. Addressing those gaps requires pairing physical deployment with demand-side policies, better measurement, and regulatory frameworks that preserve both competition and investment. With these adjustments, Europe can convert high coverage into inclusive, resilient, and innovation-friendly digital societies.

Comments

Post a Comment